Tens of thousands of tenants throughout BC live with roommates. While data is hard to come by, a few different sources paint a revealing picture: in BC in 2019, almost a quarter of renter households had roommates; in 2021 roommate households and couples without children were the fastest growing household type both in Vancouver and Canada-wide. Living with others can make a home more affordable, and provide company and community.

The problems in provincial policy

Despite the prevalence of roommates, provincial law and policy has created at least two significant problems for tenants who live with or want to live with others. The first is that when one co-tenant gives notice to end a tenancy, it ends the tenancy for everyone. That means that in a five bedroom house with five tenants, for example, just one tenant giving notice means everyone may have to leave.

While it is reasonable that someone should be able to exit a tenancy agreement with proper notice and no longer be legally responsible for it, the issue is that the remaining tenants have no right to remain in their home. Landlords regularly use this as an opportunity to demand large rent increases. Because the tenancy is ending, they are not bound by rent increase limits – rent control is tied to agreements, not units. This can have devastating consequences for tenants who have lived for years in a residence only to be forced to leave because one person gives notice.

The second significant problem is that landlords can include clauses in a tenancy agreement that require a tenant to get the landlord’s written permission for a roommate to move in. Landlords can give a warning letter and then an eviction notice to tenants who don’t obey a clause like this in their agreement.

This can put immense pressure on tenants. Landlords often use this against long-term tenants to pressure them to move or pay massive rent increases: one roommate moves out, and the landlord will only give permission for a new one if the tenant agrees to a huge rent increase. While roommates are often acquaintances or friends, they can also be someone’s partner, spouse, or even child. There is nothing in the Residential Tenancy Act to prevent a landlord from refusing to let a tenant’s spouse or child move in with them if they have a clause that limits additional occupants.

Solutions are simple

These rules interfere with the freedom of tenants to live their lives how they see fit and often tear households apart. They are also unnecessary: there are already rules and guidelines about “unreasonable” numbers of occupants living in a rental unit, and tenants are already legally responsible for any damages they, their guests or roommates cause during the tenancy beyond wear and tear. Landlords can also make tenants pay for their utilities.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Legislative changes could improve the situation for roommates. The Ministry of Housing could make it so that co-tenants can leave a tenancy without forcing the tenancy itself to end as long as at least one original tenant remains. They could also abolish occupant clauses, just as we have argued they could abolish no-pet clauses. In fact, they recently banned rent increase clauses for minors after several high-profile news stories of landlords trying to increase the rent after tenants had a baby.

Both of these changes would be straightforward to implement and would make housing more secure for the thousands of roommates in BC the instant they are made. And BC wouldn’t be the first province to do so: Ontario does not require landlord permission for additional roommates. As one lawyer puts it, “it’s frankly none of the landlord’s business who else lives in your unit.”

Ending these restrictive clauses will open up more living space for tenants by preventing landlords from denying additional occupants in units that can support them. We’ve heard directly from tenants living alone who cannot get their landlords’ permission for an additional roommate in their two or more bedroom unit without a rent increase they can’t afford. Some landlords are preventing bedrooms from being filled in the hopes their tenant will move out.

There are also individual actions tenants can take to better protect themselves. First, carefully read and fully understand any tenancy agreement you sign, paying particular attention to any clauses that restrict your ability to have roommates. Second, decide what kind of roommate you want – do you want them to be co-tenants, tenants-in-common or simply occupants? Read about their differences in our explainer. And finally, while disputes between roommates aren’t heard by the Residential Tenancy Branch, using our Roommate Agreement can nonetheless provide clarity and potential action if you experience conflict, which you could explore with the Civil Resolution Tribunal or Small Claims Court.

Not all of us can or want to rent alone. Our laws should support tenants in our varied lifestyles to live securely and affordably, not enable landlords to rent gouge and threaten eviction.

Stay updated on the latest tenancy issues by subscribing to our newsletter:

Read more

Election 2024: Where BC’s Main Parties Stand on Tenancy and Housing

The provincial election is your opportunity to shape housing policy – find out where BC’s three main parties stand on tenancy and housing.

A Provincial Call to Action on International Tenants’ Rights Day

On this International Tenants’ Rights Day, we call on BC’s government make changes needed to ensure housing is a human right.

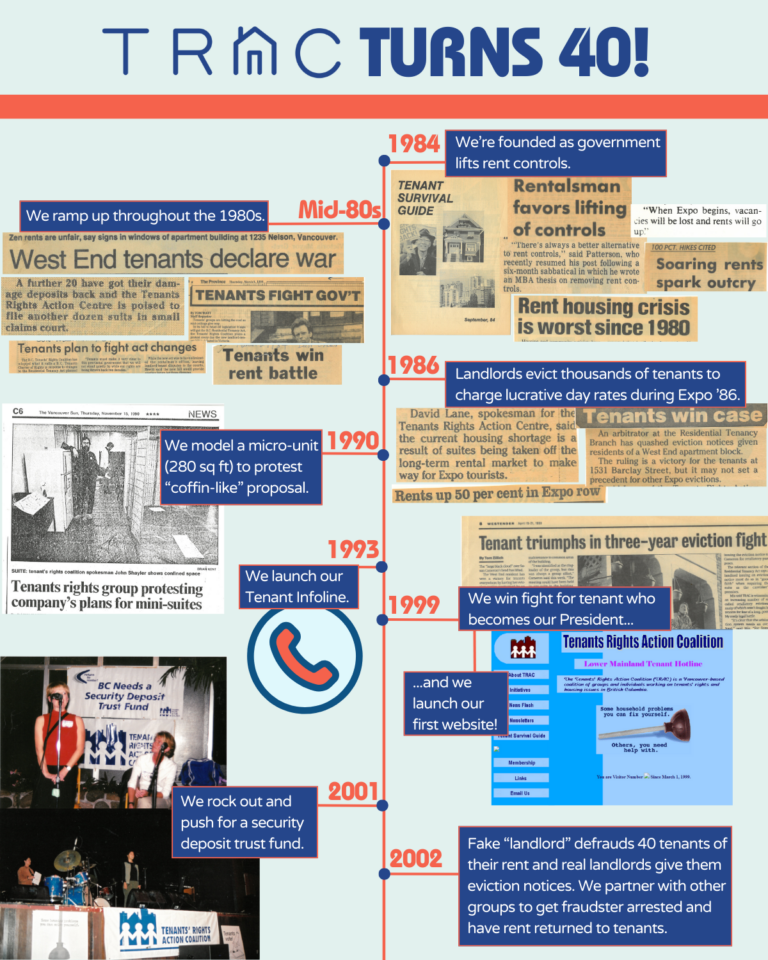

We’re turning 40!

Celebrate with us as we explore what we’ve accomplished for tenants in BC for the last four decades.